Arvind Subramanian, former Chief Economic Advisor, says in a sensational newspaper column that India’s GDP growth rate since 2011 has been only 4.5%, far short of the official 7%. Sorry, this is too bad to be true.

Many economists have castigated flaws in the new methodology for estimating GDP after 2011. In March, 108 top economists deplored political interference in compiling statistics and called for institutional independence to ensure data quality. They said GDP revisions for 2016-17 increased estimated growth to 8.2%, which was not credible since demonetisation should have caused a plunge.

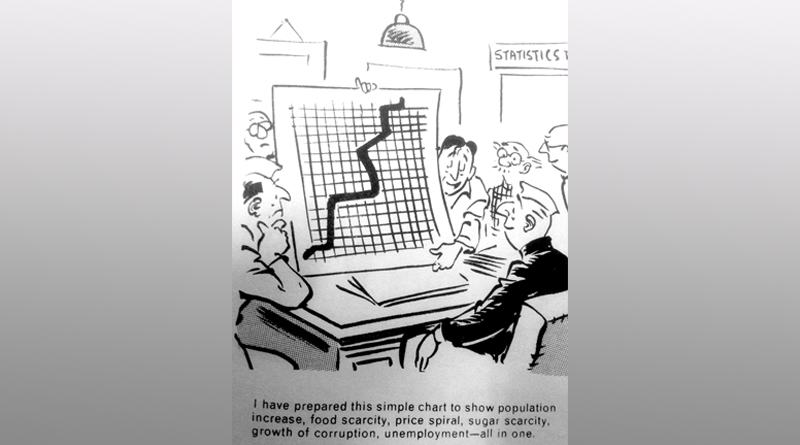

Official statistics showing that GDP growth in the Modi era was as fast as in the 2000s fail the “smell test” of credibility, say many economists. Till the financial crisis of 2008, the 2000s witnessed soaring exports, bank credit, real estate, and auto sales. Wild enthusiasm and optimism fuelled dreams of India becoming a global superpower. Such enthusiasm and optimism have been missing in the last five years, with complaints of agrarian crises, record unemployment, and stagnant exports and investment.

Doubts about official data are not new. Economist Shankar Acharya said in 2016 that India felt and smelled more like a 5% economy than a 7% one. Indeed, Subramanian himself referred to anomalies and puzzles in GDP data in the Economic Survey when he was in office.

Some say Subramanian’s sensational column is a political ploy to discredit Modi. I disagree. His research covers growth in the period 2011-16, which covers both UPA-2 and Modi-1. It suggests that GDP was exaggerated in both eras, so it is not politically slanted. The much-criticised new statistical methodology was debated widely in the 2000s and accepted by most economists, the IMF and World Bank at the time as an improvement. It was adopted by UPA-2, so it could not be a plot to taint Modi.

Subramanian has made a technocratic effort to assess our statistical credibility. In countries like China, where official data look dubious, economists often try to estimate “real” GDP by analysing the growth of top economic indicators instead. Subramanian has tried something similar in a Harvard research paper. He looks at a bundle of 17 major indicators including electricity, steel, oil and cement; rail and air traffic; indices of industrial production; bank credit, exports and imports. He finds growth is slower (often much slower) in 15 of the 17 indicators post-2011, indicating GDP deceleration.

Next, he estimates the relationship between four indicators — credit, exports, imports and electricity — and GDP for 71 countries to establish a trend line. He finds that India follows the trend line till 2011, but then deviates markedly. He believes this is mainly the result of the new statistical methodology over-estimating GDP after 2011.

He calculates what GDP growth would be had India remained on the trend line. He finds this is between 3.5% and 5.5%, or say 4.5% on average. His research makes a case for suspecting GDP is over-estimated, and needs a fresh look under a new methodology. Had he said no more than this, few would have disagreed.

But Subramanian is not just an economist. He is also a famous columnist, writing in the media to demystify economic issues for the public. And his latest column declares categorically that GDP growth has been only 4.5%, not 7%.

Sorry, but this does not follow from his research results at all. The technique of deriving estimates from a few economic indicators yields an educated guesstimate of GDP, but no more. It is definitely no way of accurately estimating GDP. Subramanian’s research may cast doubt on official statistics but is nowhere near enough to produce an authoritative alternative estimate. No country in the world uses a small bundle of indicators to measure GDP: that would be gross, misleading oversimplification.

Subramanian says his research shows that, post financial crisis, the statistical picture that India “came out with guns blazing” must give way to “the more realistic one of an economy growing solidly but not spectacularly.”

Sorry, but 4.5% is not “solid” economic growth. It is pure disaster. It is the rate of growth India had in the late 1970s. Indeed, the bottom of Subramanian’s growth range of 3.5% to 5.5% is what used to be derided as the Hindu rate of growth that condemned India to poverty for three decades.

Subramanian can certainly argue that a 7% growth claim has a smell problem. But his 4.5% estimate fails the smell test too. India has many problems but displays nothing like the economic disaster that 4.5% growth would imply.

Conclusion: the journalist in Subramanian has overtaken the economist. The outcome is not fragrant.