The election of Mallikarjun Kharge as Congress president confirms that the Gandhi family remains in charge via a barely concealed puppet. Anyone hoping Kharge will chart an independent course is a fantasist. Loser Shashi Tharoor had all the possible qualifications save the family imprimatur.

Analysts galore think the Gandhi family is a Congress liability. Rahul Gandhi seems like a pedestrian politician who cannot win elections. Sonia seems aged and unwell. Defections (cloaked as resignations) brought down Congress coalition governments in Karnataka and Madhya Pradesh and are spreading in other states. Internal warfare threatens Congress’ last two redoubts, Rajasthan, and Chhattisgarh.

Why the Gandhis matter

But to believe new Congress leaders can replace the Gandhis and capture voter imagination is a dream. The party has no ideological glue, and so suffers defections seamlessly. It includes opportunists that hate one another but stick together because the Gandhis can win them elections. Without the family their electability crashes. History proves that conclusively.

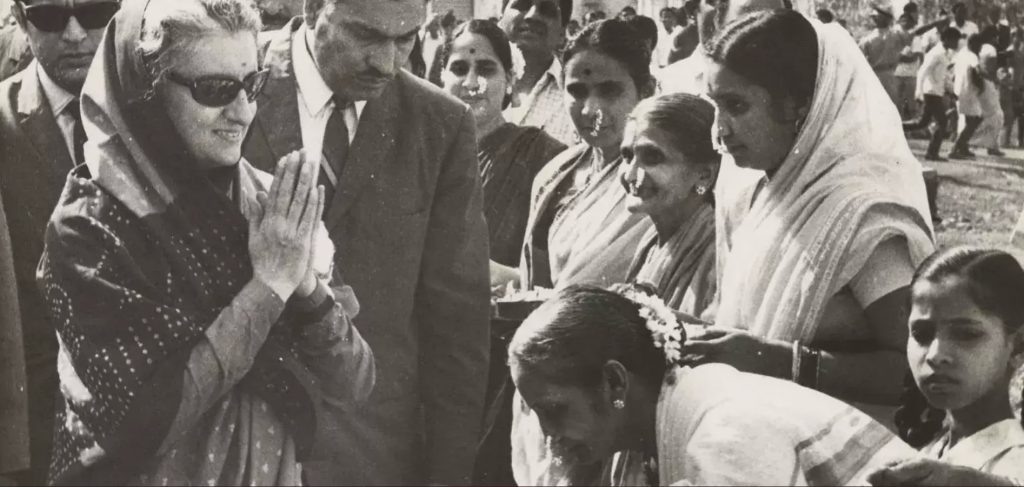

Lal Bahadur Shastri succeeded Nehru in 1964 but died in 1966. Party bosses collectively called the ‘syndicate’ chose Indira Gandhi as his replacement, expecting that the family name would fetch votes while keeping real power in the syndicate. But in the 1967 election, the Congress suffered a huge setback in Parliament and lost power in most north Indian states. Almost all syndicate honchos lost, proving that voters preferred the family to the organisation.

To crush the syndicate, Indira split the party in 1969. Her Congress (R) opposed the formal party, the Congress (O). In the 1971 election she thrashed the Congress (O) and all other parties. Voters were emphatic that the Congress meant Indira, not the regional bosses.

Something similar happened in 1977. The Emergency made Indira unpopular. In the 1977 election, the Congress (O) and other Opposition parties coalesced to form the Janata Party. Indira was thrashed. Morarji Desai, former Congress (O) head, became prime minister.

Analysts claimed the family was politically dead. Indira was ejected from leadership of her own Congress (R). She split the party again to assert control. Despite her tarnished image, voters favoured her faction resoundingly over the party-minus-family. She roared back to power in 1980.

Indira was assassinated in 1984. Rajiv Gandhi replaced her but was assassinated too during the 1991 election. Sonia refused to take his place. So, in despair rather than hope, the party selected a non-Gandhi leader, Narasimha Rao. Under him, the Congress in 1991 won 232 seats, far short of a majority. He steered his minority government through a major economic crisis, but corruption accusations hurt him badly. In the 1996 election, the Congress got just 140 seats.

Sitaram Kesri, another lightweight, replaced Rao. He too commanded little party loyalty. Defections galore hit the party in the run-up to the 1998 elections. Congressmen told Sonia she alone could save the party. She agreed to lead the party, and defections stopped immediately.

Under Sonia, the Congress won 141 seats in 1998. This fell to 114 seats in the 1999 election. Forgetting Congress history, critics declared that the family was a liability that the Congress should dump. However, Sonia then led the party to two successive victories in 2004 and 2009. The family greatly outperformed the party-minus-family.

Today critics again urge the party to dump the Gandhis. But history shows that would be folly. In other parties too, voters have preferred family leaders to party machines. In 1947 no Indian party was a family business. Today most parties are. The BJP is the great exception. The Communists are also exceptions but dying ones. India is very different from western democracies.

The problem is not autocratic leaders. Rather, voters vibe with individual politicians but not with party labels. Voters do not penalise defectors who can, therefore, rise to become chief ministers in rival parties. Personalities matter, not manifestos.

In Andhra Pradesh, one family business (Jagan Mohan Reddy) has displaced another (the Gandhis). Naveen Patnaik broke away from the Janta Dal to form a party named after his father. The Mulayam Yadavs in UP, Thackerays in Maharashtra, Lalu Prasad in Bihar, Deve Gowdas in Karnataka, and Karunanidhi offspring in Tamil Nadu are other examples of family businesses that voters swear by. Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka are also run by family businesses. This is a regional pattern.

Many deplore the success of families, just as they deplore the success of caste, religion, and regional chauvinism in politics. But in a democracy voters get what they want.

Remember that after electoral debacles Indira was written off in 1977 and Sonia in 1999, but both bounced back. Will Rahul bounce back too? It’s not impossible, but history does not always repeat itself. This time the family may fail to reverse the party’s slide into irrelevance. But without the Gandhis the process will accelerate, not reverse.