Incentives should not be extended beyond five years: the biggest risk is that they will continue forever in flop sectors to save face and jobs. Demands from additional sectors to get PLI must be resisted. 14 sectors are already too many. PLI is still likely to fail where it backs national champions for domestic sales in a protected market.

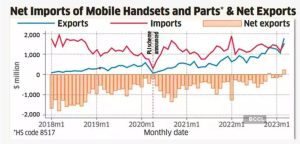

In 2017-18, India imported $21 billion of cellphones and components, and exported just $1.1 billion, for a net sectoral trade deficit of $20 billion. But exports have since soared, while imports have been muted. In March 2023, exports actually exceeded imports by $239 million, according to calculations from commerce ministry data by economist Rahul Chauhan (see graphic). This is a phenomenal reversal.

For the full year 2022-23, the trade deficit in cellphones was $3.6 billion. This looked a huge improvement over $20 billion five years earlier. But none could have expected this to turn into a net surplus by March 2023.

In 2022-23, Apple exported $5 billion of its production of $7 billion. Samsung also exported $4 billion. Apple targets $20 billion by 2024, and aims to shift 25% of its global output in India. Component suppliers – Foxconn, Pegatron and Wistron – are ramping up production in India, for cellphones and other consumer electronics.

This is a success of industrial policy, giving huge subsidies and tariff protection to select companies to create world-beating factories with global scale economies. I have always been sceptical of industrial policy. History shows that governments often fail in picking industrial winners and end up with white elephants and crony capitalists. This is what happened with the Nehru-Indira aim of creating national public sector champions.

However, the Asian Tigers – South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore – successfully used industrial policy from the 1960s onwards to create world-beating companies. They were all autocracies that, unlike India, could crush all opposition to land acquisition, environmental norms or hire’n’fire labour laws. They had small populations and domestic markets, and, hence, focused on export-oriented factories. China later followed the same approach.

But in Indian conditions, industrial policy historically failed. Why, then, has it succeeded in cellphones? In 2017-18, cellphone imports at $21 billion were second only to oil imports. Domestic production was tiny. Many local factories that once showed promise later closed. India fared poorly in electronics because it had signed the Information Technology Agreement in 1996 pledging zero duty on specified electronic items to facilitate the digital revolution.

Indian electronic manufacturers faced import duties on their raw materials and components, and so could not compete with duty-free imports. To end this reverse protection, the government announced a phased manufacturing programme (PMP) for cellphones and components in 2017, later supplemented by Aatmanirbhar and production-linked incentive (PLI).

Critics feared that cellphone manufacture would depend heavily on component imports, adding little value. Apple’s value added in India is barely 15%, though the company hopes to raise it to 20-25%. The 20% import tariff on phones means protection of ₹20 plus a PLI grant of ₹4-6 for value addition of just ₹15. Does this not mean showering billions on a few corporations for minor gains? Is it not a waste of public money? Will beneficiaries become uneconomic and close when incentives are withdrawn after five years, as scheduled?

These would be major dangers if cellphone production was for self-sufficiency. But since production is overwhelmingly for export, this resembles the Asian Tiger model. High import tariffs are not an economic cost for exported output. PLI is a cost, but is a worthwhile incentive if limited to five years. Success depends on creating massive capacities with scale economies, which will remain competitive when incentives end.

Why were pessimists proved wrong?

- Geopolitics were a new factor pushing MNCs out of China into India.

- MNCs catered mainly to the global market. So, the cellphone incentives did not mean self-sufficiency. Instead, they ensured global competitiveness.

- MNCs have persuaded state governments to relax labour laws, improving the ecosystem.

Rajan thinks MNCs may have used transfer pricing to keep profits in India during their current tax holiday, inflating their exports. I think this can only be a minor factor. Unlike Rajan, I confess I was wrong.

The outlay for PLI has been fixed at ₹1.97 lakh crore over seven years. That is barely 0.6% of GDP, very affordable even if some sectors fail. Disbursement has been slow because companies have not fulfilled PLI conditions. For success, these conditions must not be relaxed. Please stay tough.

Incentives should not be extended beyond five years: the biggest risk is that they will continue forever in flop sectors to save face and jobs. Demands from additional sectors to get PLI must be resisted. 14 sectors are already too many. PLI is still likely to fail where it backs national champions for domestic sales in a protected market.

Bottom line: PLI should create massive capacities mostly for export, not for the domestic market, as the Asian Tigers did. The aim should be globalisation, not self-sufficiency.

This article was originally published by The Economic Times on May 02, 2023.