Dear Supreme Court judges,

You have approved a 10% job and educational quota for economically weaker sections (EWS) in addition to the 49% quotas for Dalits, tribals and other backward classes (OBCs). This adds reverse discrimination on economic grounds to those on historical grounds.

In effect, you have rejected “merit” as a mirage. Indeed, one of you said that treating unequal people as equal was actually a form of inequality that is not constitutional.

Having enunciated this principle, why restrict it to jobs and education? Why not extend it to other fields? Start with cricket, which provides jobs galore directly and indirectly.

The Indian cricket team is chosen on merit. But your verdict suggests this is an illusion created by historical caste domination. How many Dalits or tribals are in the national or state teams? Very few.

You have approved a 10% job and educational quota for economically weaker sections (EWS) in addition to the 49% quotas for Dalits, tribals and other backward classes (OBCs). This adds reverse discrimination on economic grounds to those on historical grounds.

In effect, you have rejected “merit” as a mirage. Indeed, one of you said that treating unequal people as equal was actually a form of inequality that is not constitutional.

Having enunciated this principle, why restrict it to jobs and education? Why not extend it to other fields? Start with cricket, which provides jobs galore directly and indirectly.

The Indian cricket team is chosen on merit. But your verdict suggests this is an illusion created by historical caste domination. How many Dalits or tribals are in the national or state teams? Very few.

Some call Sachin Tendulkar the greatest batsman ever. But he had the advantage of being a Brahmin. Others call Sunil Gavaskar the greatest batsman. Alas, another Brahmin. In bowling, the greatest Test wicket-taker is Anil Kumble. One more Brahmin. The captain of the T20 cricket team is a Brahmin, Rohit Sharma. Ishant Sharma dominated fast bowling for a decade. Rahul Sharma has played for the Indian team and Sandeep Sharma for the under-19 team. The chief test selector is Chetan Sharma.

The coach of the Indian team, Rahul Dravid, is a Brahmin. So was his predecessor, Ravi Shastri. So was his predecessor, Anil Kumble. Not a Dalit or tribal coach in sight.

Till the 1980s, more than half of the cricketers in state teams were Brahmins. Politically, the upper castes now share power with the dominant rural castes (Yadavs, Patels, Jats), and cricket has gone the same way.

Is Suryakumar Yadav the best new batsman? Or merely the beneficiary of a system that keeps out Dalits and tribals? No less than four Yadavs have represented India this year — Suryakumar, Kuldeep, Umesh and Jayant. Ajay Yadav plays for Jharkhand and Sanjay Yadav for Tamil Nadu.

National mainstream

Some may say cricketing teams are not government institutions, and so need not have quotas. But your verdict says that EWS quotas can be extended to private unaided institutions too.

Justice S Ravindra Bhat declared, “Unaided institutions, including those imparting professional education, cannot be seen standing outside the national mainstream.”

Well, cricketing academies, college teams and state cricket teams also impart what amounts to professional education. Can they be seen standing outside the national mainstream?

Till the 1980s, more than half of the cricketers in state teams were Brahmins. Politically, the upper castes now share power with the dominant rural castes (Yadavs, Patels, Jats), and cricket has gone the same way.

Is Suryakumar Yadav the best new batsman? Or merely the beneficiary of a system that keeps out Dalits and tribals? No less than four Yadavs have represented India this year — Suryakumar, Kuldeep, Umesh and Jayant. Ajay Yadav plays for Jharkhand and Sanjay Yadav for Tamil Nadu.

National mainstream

Some may say cricketing teams are not government institutions, and so need not have quotas. But your verdict says that EWS quotas can be extended to private unaided institutions too.

Justice S Ravindra Bhat declared, “Unaided institutions, including those imparting professional education, cannot be seen standing outside the national mainstream.”

Well, cricketing academies, college teams and state cricket teams also impart what amounts to professional education. Can they be seen standing outside the national mainstream?

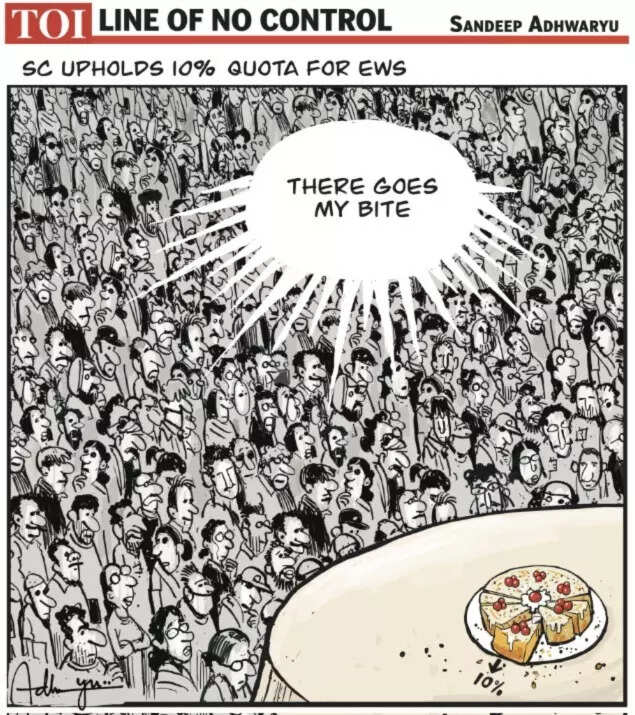

TOI cartoonist Sandeep Adhwaryu’s take on the EWS quota

Your honours, reject arguments that cricket quality will suffer. The quality argument was made to denigrate civil service quotas for lower castes, yet quality today is just fine. So, your honours, please launch a suo motu case for quotas in cricket.

Let me now halt. This open letter to the judges is only a rhetorical device. It aims to expose the folly of constantly expanding quotas. Cricket quotas would be madness. India would become an international laughing stock. A major industry would collapse, and India would be thrashed in international matches. Yet the logic of the court applies to cricket too. That explains why the logic is wrong.

In the US, racial quotas have been declared unconstitutional by the courts. Other cricketing countries have no quotas in cricket or anything else.

Quest for social justice

Why are they so different? Because they realise that every quota aimed at correcting historical injustice creates a current injustice. Upper-caste people who have never discriminated against anyone and have higher marks (or cricket scores) will lose out to those with inferior scores, and that is unjust. Maybe some current injustice is necessary to offset historical injustice. But in almost all other countries, social justice is sought through scholarships and schemes other than quotas. For those countries, mainstream justice means non-discrimination, with all its shortcomings. Quotas create too much injustice and affect excellence.

Do Indians have some superior morality that sees justice in quotas that others cannot? Only the arrogant would say so. Yet that claim is implicit in the Supreme Court’s verdict and those supporting it.

Once, reverse discrimination in India was treated as a temporary injustice required to offset the historically disadvantaged. But politically, this has become the way to win elections. Hence, reservations have constantly expanded, and no political party dares set time limits on quotas.

BR Ambedkar thought reservations for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes were needed for only 10 years, but politics has forced endless extensions. The courts should focus on the Constitution’s guarantee of non-discrimination, limiting quotas and resisting expansion. They have not done so.

One way to restore sanity is to petition the courts to immediately impose quotas on cricket. What applies to education surely applies to cricket. And yet imposing quotas on cricket would expose how deeply unwarranted such quotas can be. That might finally trigger a sober realisation of the need to minimise rather than constantly expand quotas.

Let me now halt. This open letter to the judges is only a rhetorical device. It aims to expose the folly of constantly expanding quotas. Cricket quotas would be madness. India would become an international laughing stock. A major industry would collapse, and India would be thrashed in international matches. Yet the logic of the court applies to cricket too. That explains why the logic is wrong.

In the US, racial quotas have been declared unconstitutional by the courts. Other cricketing countries have no quotas in cricket or anything else.

Quest for social justice

Why are they so different? Because they realise that every quota aimed at correcting historical injustice creates a current injustice. Upper-caste people who have never discriminated against anyone and have higher marks (or cricket scores) will lose out to those with inferior scores, and that is unjust. Maybe some current injustice is necessary to offset historical injustice. But in almost all other countries, social justice is sought through scholarships and schemes other than quotas. For those countries, mainstream justice means non-discrimination, with all its shortcomings. Quotas create too much injustice and affect excellence.

Do Indians have some superior morality that sees justice in quotas that others cannot? Only the arrogant would say so. Yet that claim is implicit in the Supreme Court’s verdict and those supporting it.

Once, reverse discrimination in India was treated as a temporary injustice required to offset the historically disadvantaged. But politically, this has become the way to win elections. Hence, reservations have constantly expanded, and no political party dares set time limits on quotas.

BR Ambedkar thought reservations for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes were needed for only 10 years, but politics has forced endless extensions. The courts should focus on the Constitution’s guarantee of non-discrimination, limiting quotas and resisting expansion. They have not done so.

One way to restore sanity is to petition the courts to immediately impose quotas on cricket. What applies to education surely applies to cricket. And yet imposing quotas on cricket would expose how deeply unwarranted such quotas can be. That might finally trigger a sober realisation of the need to minimise rather than constantly expand quotas.

This article was originally published by The Times of India on November 12, 2022.