Had distress been driving poor people to work, Female Workforce Participate Rate would have risen fastest for the poorest deciles of the rural population. In fact, rise has been slowest for the poorest decile, from 16.5% to just 19%. It has risen fastest for the top two deciles, from 19.4% and 19.9% to 32.6% and 33.5%, respectively. This is encouraging.

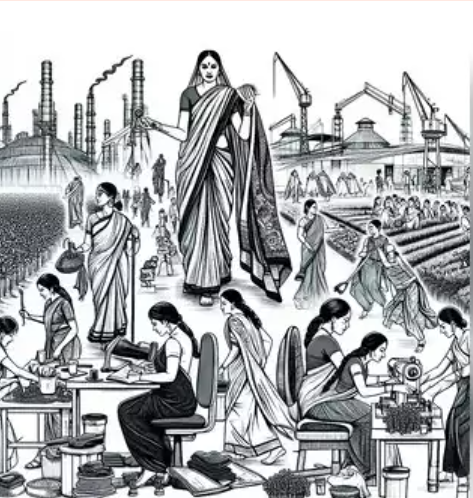

Female workforce participation has risen sharply since FY17, after declining for three decades earlier. This should mean higher incomes, even if real rural wages have stagnated. Free foodgrains would have further improved real income.

But critics, including Radhicka Kapoor, Ashwini Deshpande and authors of Azim Premji University’s ‘State of Working India Report 2023’, interpret rising female work participation rate (FWPR) as distress, not prosperity. They point out that rising FWPR has been mainly in agriculture, a low-productivity occupation. Higher rural employment (including MGNREGA) could represent distress as people who had earlier withdrawn from the workforce were obliged to return.

The bulk of higher FWPR came from a sharp increase in unpaid self-employed women. Critics say this could imply lack of jobs and disguised unemployment.

Others, such as chief economic adviser Anantha Nageswaran, have more optimistic explanations. They point to rising multidimensional indicators for women, which is not consistent with distress. For women, the proportion in agricultural work entailing heavy manual labour is down from 23.4% to 16.6%, while the proportion in skilled agricultural work rose from 48% to 59.5% between FY19 and FY23.

Underlying trends are difficult to establish in an economy repeatedly hit by external shocks. India was hit by Covid in 2020, the Ukraine war in 2022, and El Nino in 2023. These shocks have certainly caused distress. But that should be temporary. We need several more years of data to conclusively untangle the impact of shocks from deeper underlying trends.

However, a recent paper by Bishwanath Goldar and Suresh C Aggarwal of the Institute of Economic Growth presents a strong case for optimism. FWPR declined from 32% in FY94 to 20% in FY18, but then rose sharply to 28% in FY23.

The earlier decline was widely mourned as wasting India’s demographic dividend. By the same token, the recent sharp rise should be called a welcome revival of the dividend. Instead, critics find distress in both the earlier decline and recent upsurge, with no sense of irony.

Between FY20 and FY22, rural men in agriculture declined by 13.3 million, and increased by 18 million in non-agricultural activities. Meanwhile women in agriculture increased by 22 million. So, the vast majority of higher female employment appears to be replacement for men who are going into higher-productivity industry and services.

Chandra Bhan Prasad says that in some villages, every single household has at least one male member who has migrated to a town and is sending home remittances. This is very positive. Goldar and Aggarwal say economic reforms have accelerated manufacturing employment, which grew by 4.7% in FY21 and 8.2% in FY22. This is unprecedented, they say. Employment rose a whopping 25% a year for enterprises with 10-19 workers, reflecting robust formalisation.

Khadi and Village Industries Commission (KVIC) accounts for a significant proportion of unorganised manufacturing and jobs. Employment in this sector rose 28% between 2015 and 2022. This would account for an increase in the proportion of women in manufacturing and services rising from 9.5% to 13% between FY18 and FY22.

Had distress been driving poor people to work, FWPR would have risen fastest for the poorest deciles of the rural population. In fact, rise has been slowest for the poorest decile, from 16.5% to just 19%. It has risen fastest for the top two deciles, from 19.4% and 19.9% to 32.6% and 33.5%, respectively. This is encouraging.

Goldar and Aggarwal believe conditions for women to work have improved because of better infrastructure and reduction of crime in states like Uttar Pradesh. The programme for piped water to all rural households has released women from fetching water from distant sources. One study suggests that a reduction of 100 minutes in household chores raises FWPR by a whopping 10%.

In UP, FWPR is 38% in places where over 90% of households have running water, but drops to just 15% where less than half the households have piped water. So, piped water, along with cooking gas and electric appliances, is helping raise FWPR.

Cellphones have improved information and raised employment by better matching seekers of work and hirers. Financial inclusion has improved financial security. Fintech companies, microfinance companies, self-help groups and MUDRA loans have provided more finance than ever before for rural activity. Animal husbandry is among the fastest rising sectors in agriculture, has relatively high productivity, and is typically done by women.

Finally, reports across India speak of a serious labour shortage in agriculture despite the increase in labour supply. This is not compatible with the theory of distress.

Rural real wages may have stagnated in recent years, but urban real wages have risen appreciably. The old distinction between rural and urban areas is breaking down. With better transport and digitisation, all rural areas within 60 km of a town are developing strong urban linkages. Rural migrants to distant cities earn far more than in farm work. This enables them to send home remittances, improving rural spending power.

In sum, the case for interpreting a rising FWPR as distress is very weak. The case for optimism is far stronger.