The good news is that cases of kala azar have crashed 98.7%, from 44,533 in 2007 to just 834 in 2022. Hopefully, it will be eradicated in a few years.

Because kala azar is little known in urban metros, the news has not made big headlines. But for those in some of the poorest parts of India, where there are so many ways to die, there will be one less. India has already eradicated smallpox, polio, and guinea worm. Kala azar could be the fourth disease to be eradicated.

India has been a laggard in combating infectious diseases. For a country that aspires to be a world leader, its performance has been an embarrassment.

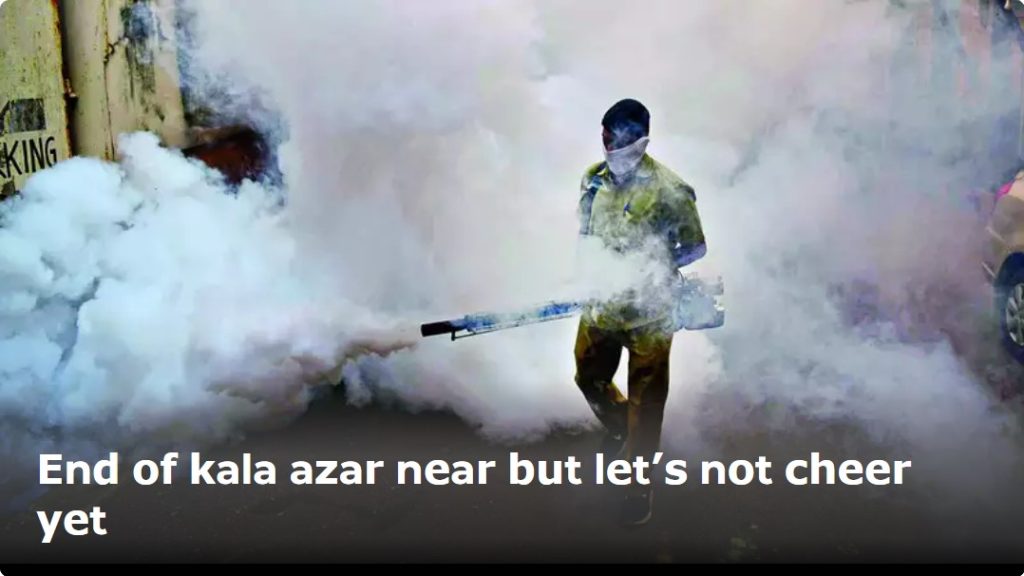

The main way of controlling the sand flies that spread the disease is indoor spraying of houses with synthetic pyrethroid, which has replaced Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) as the main way of combating mosquitoes and sand flies.

Mud houses are highly prone to sand fly infestation so building brick houses under the PM Awas Yojana — intended mainly for improved housing — has the incidental advantage of reducing kala azar too. For those already infected, accurate diagnosis is vital since it is often mistaken for malaria and the wrong medicine may be administered.

Why it’s taken so long

Awareness and consumer education is vital, without which prevention will not work. Practitioners speak of resistance from households, especially in tribal areas, to indoor spraying of insecticide since it leaves a bad smell. Awareness and education are needed to convince people that temporarily enduring a foul smell is better than risking blackening of the skin followed by death.

The worst-affected areas are also among those with the weakest administration, notably north Bihar. Eliminating the disease should not be difficult because the ways of doing it are well established. But it requires systematic planning and implementation, coordination between different agencies, updating of technological improvements, good logistics, and good monitoring and supervision. Good equipment is needed to spray the insecticide uniformly and comprehensively and this is not always available. States that are poorly administered are, almost by definition, poor in public health management too. That is why the elimination of kala azar has taken so long.

The Bihar government claims that it has eradicated kala azar in all blocks. Yet the official figures show Bihar had 547 of India’s 834 cases in 2022, so declaring victory is premature. However, the state’s case load has certainly fallen from 7,615 cases in 2014. Victory is not far off.

Mud houses are highly prone to sand fly infestation so building brick houses under the PM Awas Yojana — intended mainly for improved housing — has the incidental advantage of reducing kala azar too.

The last mile challenge

By international convention, a region has to be free of infection for three full years before it can be declared disease-free. The government can legitimately claim it is on the verge of a major breakthrough. But caution is advisable. Progress in the 1990s had led to 2010 being set as the target date for eradication of kala azar. Alas,13 years after that deadline, the disease has not yet been eliminated. Completing the last mile has proved difficult, and the disease may yet bounce back.

When India became independent in 1947, the population was an estimated 330mn of whom as many as 75mn per year went down with malaria. The Malaria Eradication Programme, based largely on indoor spraying of DDT, reduced cases to just 1,00,000 by 1964, and eradication seemed round the corner. But then mosquitoes became DDT-tolerant, and DDT became discredited as an insecticide because it was also an environmental hazard. Other insecticides were used but did not have the same effect, and systematic indoor spraying withered away.

By the 1970s, malaria had returned in a big way. The caseload shot up to a peak of 6.4mn. It diminished gradually after that. India had 1.1mn cases in 2014, but that came down dramatically to just 1.6 lakh in 2021. The government’s target date for malaria eradication is now 2030, and that seems feasible. But past experience shows that diseases can bounce back with a vengeance. Eternal vigilance is the price of eradication.

Let us cross our fingers and hope that kala azar is eradicated within the next two years, and malaria by 2030. Even if we succeed, do not cheer too loudly. Other countries eradicated these diseases long before us. India has been a laggard in combating infectious diseases. For a country that aspires to be a world leader, its performance so far has been an embarrassment.