This was arguably the least populist election budget for decades, and that is an achievement. Most budgets are notable for what they do. This one is notable for what it did not. It did not decree a farm loan waiver or interest-free farm loans. It did not announce new freebies. It did not revive subsidies for petrol and diesel to offset rising import costs. It did not grant the middle class higher income-tax exemptions.

It did indeed outline what it claims could eventually become the world’s biggest healthcare scheme. But the budget provision for this was peanuts, just Rs 2,000 crore. Talk of this being ‘Modicare’ to rival Obamacare is fanciful. Obamacare provided universal coverage, while this is limited to 100 million poor households, and to hospitalisation for major diseases, not all sickness. Even for this, India does not have remotely enough hospitals or doctors. India certainly needs far better public healthcare, but the budget proposal is rhetoric unbacked by cash.

Budget rhetoric on rural revival was also unbacked by dramatic spending increases. Indeed, overall spending will rise only 10.1% in an election year, less than nominal GDP growth of 11.5%. This is not populism. Nor is it a rural game changer.

The budget has two major flaws: fiscal slippage, and a return to failed import substitution policies of yesteryear. The Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act mandated cutting the fiscal deficit to 3% of GDP and the revenue deficit to zero by 2008. When Arun Jaitley became finance minister, he promised to achieve the 3% target in three years. He has now postponed getting to 3% to 2020-21, his third postponement in five budgets. This dents his credibility.

Worse, the revenue deficit will be a high 2.2% of GDP next year, nowhere near the promised zero. The quality of government borrowing is falling: too much is going for non-productive purposes. No wonder interest costs now gobble up over 35% of tax revenue. Interest rates on gilts have risen sharply in recent months, and rose further after the budget.

BJP supporters shrug off criticism of fiscal slippage as “fiscal fundamentalism”. But Jaitley never took that line in any budget speech. He promised fiscal consolidation, set targets, but then slipped. This suggests poor budgeting, poor implementation, or both.

GDP is expected to boom by 7.5% next year, and major economies across the globe are booming too. At this stage in the global business cycle, fiscal deficits should be falling fast. If India is in such fiscal stress in a boom, what will happen when the tide turns?

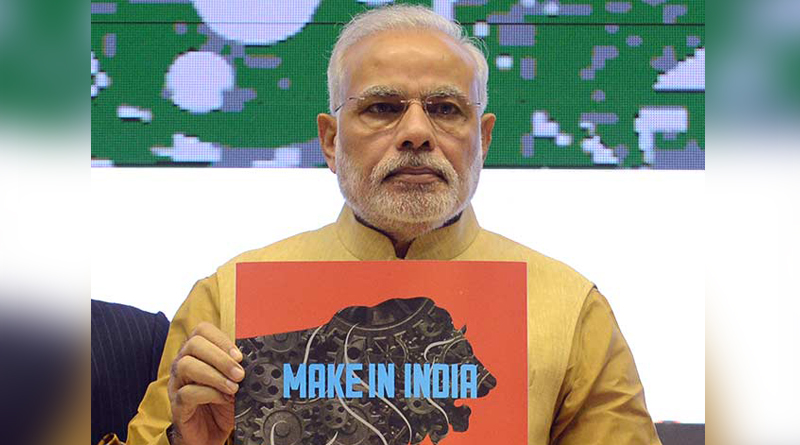

At Davos, Narendra Modi lambasted President Trump for protectionism, and pledged to back globalisation. Alas, this budget has raised protectionist import duties, from around 10% to 15-50%, on dozens of items from electronics, toys and auto parts to furniture, processed foods and a long list of consumer goods. This comes on top of pre-budget tariff increase in electronic and agricultural items Forget Modi’s Davos speech, the budget out-Trumps Trump. His ‘Make in India’ scheme is becoming a ‘Protect in India’ scheme. In theory, temporary protection for infant industries can help create scale economies. But most industries getting protection are geriatrics, not infants. Nor do the import hikes have a sunset clause to ensure they are temporary. Former Niti Aayog chief Arvind Panagariya has rightly lambasted this return to import substitution, which failed dismally in the past.

The Sensex crashed 800 points on Friday. Only a small part of this was due to the re-introduction of long-term capital gains on shares at 10%. This is a very moderate measure, since capital gains up to January 31 will be tax-free. Corporate tax was cut to 25% for companies with sales of up to Rs 250 crore, but this left out the big companies who matter most. The Sensex crash reflects unease with the overall direction of economic policy.

The budget has two other heartening features that have escaped attention. One is permission to use fixed-term labour contracts for all industries, a liberalisation of labour laws that could spur employment and investment. A 12% provident fund subvention for new employees has been extended to all industries, and should encourage hiring in the formal sector.

Another potentially important measure is the creation of 22,000 market centres where farmers can sell directly to bulk buyers, breaking the shackles of the infamous APMC Act. If state governments cooperate, this could become an important reform.

In sum, the budget has some good features, but also major flaws. The BJP looks confused and vacillating as it prepares for the next election. That will dent its performance, but should not be fatal.