Bangladesh’s social indicators beat India’s hollow. It has lower fertility, higher life expectancy, high female workforce participation and, hence, stronger female empowerment. These have underpinned its miraculous economic rise.

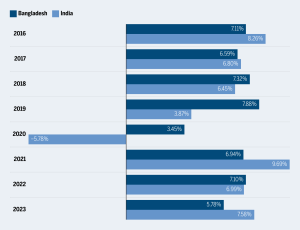

Once viewed as a basket case, Bangladesh has created a world-class ready-made garments (RMG) industry that now exports more than India. This has been a key driver of the country’s near-miracle growth rate of 6.5% per year since 2000. Its per capita income is $2,600, as high as India’s. But its miracle story is ending — it has sought

IMF assistance and has 9.4% inflation.

The RMG employs 4 million women directly and another 4 million indirectly. Giant factories employ over 10,000 each. Many economists have urged India to follow Bangladesh’s labour policies such as easy hiring and firing and flexible hours.

The formal sector in Bangladesh is not as heavily burdened as in India with non-wage costs such as contributions to an employee’s provident fund, pension scheme, health insurance, and leave travel allowance, apart from various kinds of leave.

These perks for India’s unionised labour make it uneconomic for Indian companies to employ thousands of women in RMG factories. All major Indian parties have trade union affiliates. BJP has the biggest union of all, the BMS. Hence, abolishing organised labour’s perks is politically impossible.

The RMG industry, which accounts for 84% of its exports, did not exist in Bangladesh and so had no protectionist lobby in the 1990s, when people bought cloth and had it tailored. This made it politically easy to create special free-trade zones for RMG, with bonded warehouses for duty-free imports and assured credit to exporters.

But Dhaka failed to extend this approach to other labour-intensive industries such as footwear, agro-processing and plastic products because of strong domestic lobbies favouring high tariffs. These sectors have, therefore, missed out on the cheap-labour export bus.

Zaidi Sattar, chairman of the Policy Research Institute of Bangladesh, says this is because the country is instinctively protectionist and socialist. Mujibur Rahman, father of the nation, was a strong socialist, and his party retains that rhetoric.

The resulting failure to diversify exports is one reason for Bangladesh’s current crisis, which includes loans from the IMF and high inflation.

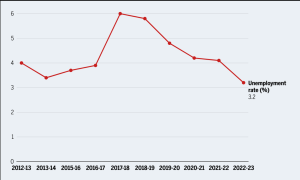

Indian economists worry that a large proportion of India’s workforce is still in agriculture instead of moving into labour-intensive manufacturing, as in Bangladesh. I have long argued that India missed the labour-intensive bus decades ago, and cannot catch it now that perks have made formal sector wages too high. Besides, Bangladesh has not done that much better: the proportion of its workforce in agriculture in 2022 was 37% against India’s 42%.

A separate problem is the rise of the educated unemployed, who do not want to work in garment factories and try desperately to get prized govt jobs. In India, this has driven the demand for job reservations from all castes, sub-cases, and religious groups. By surrendering to such demands in stages, hope has been kept alive for the educated unemployed.

But in Bangladesh, job reservation is very unpopular. It has been weaponised politically by Hasina’s Awami League — the quota beneficiaries, children and grandchildren of 1971 freedom fighters, are Awami League sympathisers. This has angered students outside her political circle, and they have revolted.

Job quotas have not been similarly politically weaponised in India which, therefore, sees student ferment but no revolt. And while Bangladesh’s extreme export dependence on one item—RMG—has brought a seeming end to the Bangladeshi economic miracle, India has a highly diversified export basket, above all, in services.

The political difficulties that make low-wage manufacturing impossible in India do not apply to services. They have helped India soar while Bangladesh has crashed. Services cannot quickly absorb all the educated unemployed, or all those in agriculture. These problems will remain. But services have shown a way forward. They should help India avoid the student revolts that have toppled rulers in Sri Lanka and Bangladesh.