In earlier columns, I have highlighted the sad slump in India’s global rankings on various measures of democracy, freedom and human rights. Economic trends have been muddied by an unexplained slump – part of a global slump – in 2019-20, followed by the disruptions of Covid and the Ukraine war. The jury is still out on whether India can return to its old miracle economy status of sustained 7% GDP growth.

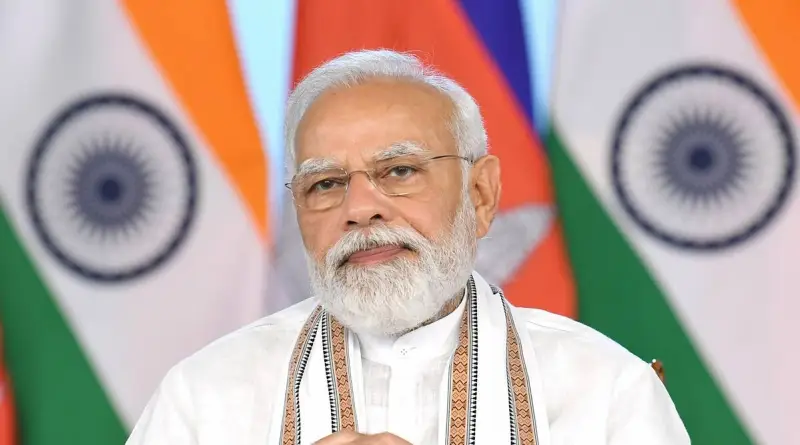

Meanwhile, industrialist Harsh Goenka, an admirer of Narendra Modi, has circulated a list of indicators of India’s economic position in the world since 2014. This shows India in an exceptionally good light. Is this accurate and realistic?

Lonely at the Top

Consider the World Bank’s latest growth projections for 2022 and 2023 in its Global Economic Prospects. This shows world GDP slowing dramatically in 2022 to 2.9% from 5.7% in 2021, thanks to the Ukraine war and central banks’ monetary tightening to combat inflation.

The world may suffer an inflationary recession. However, India will suffer less than others. The Bank projects India to be the fastest-growing major economy in 2022 (7.5%) and 2023 (7.1%). For the first time in history, India is pulling up the entire world economy, if only by a bit. This is an impressive achievement. It may surprise readers groaning about high inflation and slowing growth. But India’s problems are less than elsewhere.

China, the earlier world leader, is projected to grow at only 4.3% and 5.2% in 2022 and 2023 respectively. The only country that comes close to India in 2022 is Saudi Arabia at 7% because of a temporary oil boom. But that will dip to 3.8% in 2023. Bangladesh, which once threatened to overtake India in per-capita income, continues to show impressive strength, with projected growth rates of 6.4% and 6.7% respectively. Others lag far behind.

The World Bank has lent credibility to Goenka’s claim of India moving up in the world, despite the latter having some minor errors. India’s governance indicators have not leaped up. The World Bank’s six governance indicators for India are mixed and show little overall change since 2014. The number of unicorns, with the addition of edtech startup PhysicsWallah last week, is now 101, up from 4 in 2014. India’s weight in the emerging market (EM) index as of December 2021 was 12.5%, up from 6.6%. India’s share of world foreign direct investment (FDI) is 5.1%, up from 2.1%. Its GDP rank in 2014 was 8th; now it’s an impressive 6th. India has, indeed, improved.

But some major caveats are in order. The Yale-Columbia Environmental Performance Index (EPI) 2022 released earlier this month puts India last in the world at 180th position. The government has protested against the index methodology, castigating the high weight given to being carbon-neutral by 2050.

However, India’s position on this index was 168th even in 2020 and has never been above 150th. Let’s face it, India is a filthy country. Even if you ignore carbon and other climate change indicators, India will rank low on the quality of air, water, soil quality, aquifers and urban waste management. Nitpicking about index benchmarks cannot cloak India’s stench and filth.

Work Hard, Study Harder

In the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business index, India may have jumped up from 142nd position to 63rd, but that index has been tainted by scandals on influence-peddling and manipulation, leading the Bank to abandon the index altogether.

ndia’s foreign exchange reserves are the fourth-largest at $600 billion. This is more than double the $290 billion in 2013 when India was hit by a ‘taper tantrum’ that saw the rupee crash from ₹55 to ₹68 to the dollar as foreign investors fled for the safety of the US dollar. Today, EMs are once again in peril. But India looks relatively secure because of its high reserves.

India has three major black spots. One is the disgraceful state of education. In the international school competition, Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), in 2009, India came 72nd out of 73 countries. Reports of the NGO Pratham suggest that school outcomes have not improved significantly in the last decade. University quality is often abysmal, producing unemployable graduates.

A second black spot is inflation. India has long had the highest inflation among major economies. Currently, the US and Britain are experiencing very high inflation, higher than India’s consumer price inflation (CPI) of 7.04%. But India’s GDP deflator, the widest measure of inflation, remains a terrible 10%.

A third black spot is unemployment and a falling labour participation rate. India is supposed to be reaping a demographic dividend as the proportion of people of the working age of 15-65 years reaches a peak. But instead of shooting up to 60% as in other miracle economies, India’s labour participation rate has fallen to around 40%. Female labour participation fell to just 16% in 2020, partly because of Covid, lower than even Saudi Arabia’s rate. If India cannot get its women and working-age men into productive activity, it cannot become a miracle economy.

This article was originally published in The Economic Times on June 14, 2022