Will this interim budget really be a bore? After all, this is an election year. But the BJP is so certain of winning that it has no need to look to the interim budget for votes. Sitharaman will doubtless talk of new schemes and higher welfare allocations for every possible section of voters

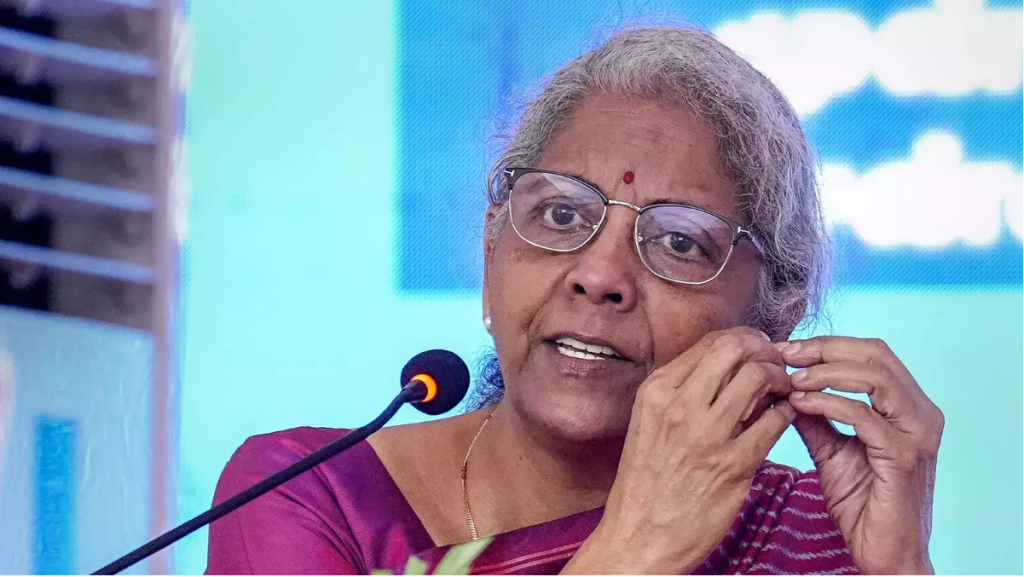

Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman will present an interim budget for 2023-24 on February 1. The full budget will be presented after the elections, in July. Do not expect fireworks in the interim budget. Finance ministers have been known to slip minor concessions into them but mostly they have kept their ammunition dry, reserving it for the full budget in July.

An interim budget is supposed to be the most boring of budgets, providing little more than a provisional statement of anticipated revenue and spending in 2023-24. It is not supposed to have tax changes that can influence voters. Yet promises can be made about the future if the party is re-elected. The general election is due in May, and every little government promise will attract attention. The interim budget will be a major media event, regardless of predictions of being boring.

In no country is the budget as huge a media event as in India. Before economic liberalisation in 1991, Indian budgets captured a limited audience on budget day, followed by a few clarifications and discussions the next day. That was all. But when Manmohan Singh presented his first budget in 1991, it was more than just a budget: it was an occasion for announcing major economic reforms and changing the entire path of the licence-permit raj that had hitherto prevailed.

The fact that no party had an absolute majority for two decades after 1991 meant that governments were never safe. The combination of reforms and political excitement helped promote budget as a must-see event.

All opposition parties, especially the leftists, claimed that India was succumbing to neo-colonialism by accepting the stringent condition laid down by the International Monetary Fund for its rescue loan. They contemptuously rejected the notion that reform was good for India. Every successive Manmohan Singh budget contained further reform proposals, which were met with similar furious castigation by the Opposition. Narasimha Rao ran a minority government that was always in danger of being toppled, so the budget had possible political consequences too. No wonder every budget attracted more eyeballs.

This was accompanied by the rise of private TV channels. They needed to increase their viewer base as fast as possible, and found that the budget could be talked up as a huge game-changer to be discussed sector by sector in search of new reforms. Excitement mounted in the month before the budget and subsequent weeks. The fact that no party had an absolute majority for two decades after 1991 meant that governments were never entirely safe. The combination of reforms and political excitement helped promote the budget as a must-see event.

This was buttressed by the rise of business TV channels that tracked every move of the stock markets. The tiniest political statements could move the market up or down. A rising middle class was increasingly investing in the stock market, and so watched every prediction and listened to every rumour. Mere speculation on policy changes could move share prices up and down by large amounts.

In this manner, the budget gained ever-rising viewership and accompanying advertisements. So, they had every incentive to find new angles and audiences.

I suspect Sitharaman will be high on rhetoric about the Modi government’s achievements but not on tax sops. Narendra Modi has always believed that elections are won by performance, not freebies.

Economic journalists found themselves in high demand. On one occasion, a journalist signed a contract with a TV channel for appearing for four days before the budget, on budget day, and again for two days after. The channel anchor was even asked about why there was a need for post-budget discussions on two more days when everything had already been discussed threadbare? The anchor laughed and said he agreed, but the channel had already received so many advertisements for the two post-budget days that they had to come up with some matching content!

Will this interim budget really be a bore? After all, this is an election year. But the BJP is so certain of winning that it has no need to look to the interim budget for votes. Sitharaman will doubtless talk of new schemes and higher welfare allocations for every possible section of voters. Like her predecessor in 2019, Piyush Goyal, she might tweak the income-tax rebates without changing the overall tax structure. Another predecessor, Jaswant Singh in 2004, announced excise duty cuts for items of common consumption on January 8, well before the budget and so skirted the prohibitions of an interim budget. This is no longer possible — excise duty has been amalgamated in the General Goods and Services tax.

I suspect Sitharaman will be high on rhetoric about the Modi government’s achievements but not on tax sops. Narendra Modi has always believed that elections are won by performance, not freebies. The finance minister is likely to be guided by that approach.

This article was originally published by The Times of India on January 6, 2023.