Traditional data cannot capture the fantastic growth of globalisation through digital services. Much of it is free, and traditional statistics simply cannot capture the invaluable addition to human welfare through free services. ChatGPT has even made AI available to billions free of charge, an astonishing form of instant globalisation.

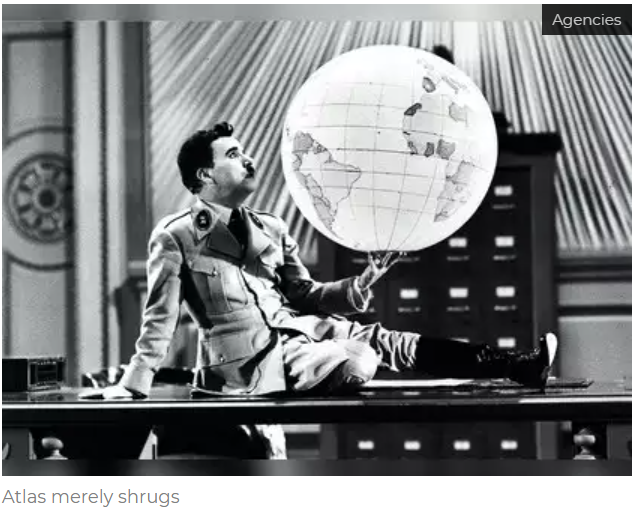

Sundry analysts predict the death of globalisation for both economic and political reasons. They claim that a new Cold War between the China-Russia axis and the West means a fracturing of trade, investment and value chains. Political efforts at reshoring and friendshoring – sometimes called a ‘China Plus One’ approach – aim at gaining security in supplies, eliminating equipment that may have spying devices, and denying China machines and knowhow for top-end equipment.

The US, Europe and India are subsidising RE investment massively, buttressed by higher import duties, to encourage import substitution. Joe Biden has proposed a $624 billion package over a decade to spur hi-tech investment.

Former RBI governor Raghuram Rajan has reviewed two books on the retreat of globalisation in Foreign Affairs. One is Homecoming: The Path to Prosperity in a Post-Global World by Financial Times journalist Rana Foroohar. The other is The Globalisation Myth: Why Regions Matter by US Council on Foreign Relations vice-president Shannon O’Neil. Rajan says, ‘Both authors foreclose the notion of a world entirely open and connected by trade: in their view, globalisation is passe, and a fragmented future lies ahead. Their claims certainly reflect a growing consensus.’

I strongly contest the notion that globalisation is passe, for two reasons:

Glocalisation: Only a small fraction of economic activity has ever been globalised. And even the ‘globalised’ part has always been mostly within regions rather than across them.

Manufactured exaggeration: While many politicians and analysts are anxious about losing manufacturing plants and jobs to China, manufacturing accounts for a small, shrinking share of GDP globally, especially in rich nations. The services sector has been gaining ground steadily. Globalisation is growing explosively in digital services, even as it reduces a bit in manufacturing.

Foroohar is an old-style nostalgist, yearning for the good old days when most manufacturing was local. Nostalgia is a poor substitute for economic sense. Foroohar thinks production can be restored to local communities by greater use of new technologies like 3D printing and vertical farming. This is desperation parading as analysis.

3D printing was launched with much hype a decade ago, but has failed to gain traction since it is totally unsuited for mass production. Vertical farming is very costly and energy-intensive, and must be avoided in a climate-sensitive era.

Food should be produced where it has the highest yields and least energy needs for growing. The cost of transporting food thousands of miles by sea is peanuts. Trying to grow food locally everywhere will mean a sharp drop in global production, food scarcity and inflation that hits the poor most, and more deforestation to farm additional land to compensate for low local yields. Foroohar’s supposed solution is crazy.

O’Neil is on stronger ground in arguing that most international trade has always been regional. The US trades mostly with countries of the Western hemisphere, above all, Mexico and Canada. European countries mostly trade with one another. Earlier, Japan, and now China, have created a ‘flying geese’ pattern of production where the lead country flies in tandem with suppliers from neighbouring Asian countries.

Cutting trade with China will surely affect global growth. But by much less than is imagined. This is because the bulk of GDP is now services.

The share of services is 82% in the US, around 75% in most European countries, and 70% in Japan. The share of manufacturing is 20% or less. So, a bit of reshoring and friendshoring in manufacturing will not make a great impact on world GDP, which increasingly represents services.

The ratio of goods trade-to-world GDP has stagnated since 2008, but that of services exports is booming, and of digital services is exploding. India accounts for only 1.5% of global goods exports, but more than 4% of global service exports. In 2022-23, India’s service exports soared by 27% to $323 billion, while goods exports rose only 6% to $447 billion. At this rate, service exports will overtake goods exports in four years.

The hottest sector is digital services, trade in which has tripled globally and risen five-fold in IT services between 2005 and 2021. Zoom has replaced traditional meetings with huge savings on travel. People in small Indian cities can listen to the greatest political experts, economists, scientists, musicians, doctors and other eminent people. They can watch cricket, football, tennis and a wide variety of sports across the world, for trivial prices. Indian yoga sites can train learners across countries.

Online gaming – and pornography – is extremely global. Netflix, YouTube, TikTok, Disney, Wikipedia, Orbitz and social media have revolutionised world trade in messaging, entertainment, and the sharing of knowledge and culture. The world can now sample Korean films, Thai cooking classes, European Renaissance art, Zulu music, Beethoven, Taylor Swift, Russian history and ‘Islamic architecture’ practically free. This is spreading culture globally as never before.

Traditional data cannot capture the fantastic growth of globalisation through digital services. Much of it is free, and traditional statistics simply cannot capture the invaluable addition to human welfare through free services. ChatGPT has even made AI available to billions free of charge, an astonishing form of instant globalisation.

So, do not mourn the death of globalisation. Whether you like it or not, it is alive and kicking.

This article was originally published by The Economic Times on December 20, 2023.