Synopsis

Radical changes are unavoidable for a bankrupt country, as India was in 1991. But not for a country averaging 6.5-7.0% GDP ‘miracle’ growth for two decades, through serious crises like the Great Recession and Covid.

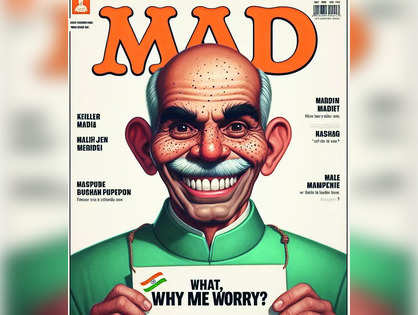

When you are faring very well, why rock the boat? Rarely has the Indian economy looked so good to global analysts. Yet, complaints galore have followed the budget presentation. Why has it not combated weak consumption? Or weak private sector investment? Or weak employment?

These complaints miss the larger picture. India is doing too well for politicians to seek major changes. Radical changes are unavoidable for a bankrupt country, as India was in 1991. But not for a country averaging 6.5-7.0% GDP ‘miracle’ growth for two decades, through serious crises like the Great Recession and Covid. This has drawn praise from global quarters. So, why attempt big reforms that necessarily carry risks, as BJP found when attempting reforms in land acquisition and farming?

No matter how weak one may view consumption, private investment or employment today, they have not constrained long-term ‘miracle’ growth. All three parameters go up and down, but are overall in sync with it.

Fragmentation of the world economy, rise of regional military conflicts and climate change mean IMF and other global institutions anticipate a global slowing. That will make even 7% growth difficult. Aiming for anything more is too risky.

Last year’s GDP growth of 8.2% may be a statistical outlier. Critics have entered a range of caveats – the GDP deflator of 1.5% looks very low, merchandise exports have actually fallen, and the GDP boom is not mirrored in the modest improvements in finances of many corporates, notably FMCG companies. Arvind Subramanian and Josh Felman have written a series of papers in recent years arguing that the GDP figures are not consistent with many other indicators showing more moderate growth.

However, former chief statistician Pronab Sen is categorical that there is no attempt to fudge GDP data. Indian statistics certainly have flaws that need to be rectified with better methodologies, higher outlays, more staff and better training. Even so, independent critics suggest that any overestimation may not be more than 0.5%. If so, the India growth story is very much intact.

In sum, whatever the current weakness of employment, consumption or private investment, the medium-term trend is consistent with GDP growth of 6.5-7.0%. It would, of course, be splendid to have higher rates. But this will be attempted through tweaks and the marketing of ‘solutions’ that are mainly illusions (as in the budget’s employment incentives).

What could be done to stimulate consumption today? Cutting taxes will improve consumption but prevent fiscal consolidation, which is badly needed. Easy monetary policy could stimulate demand, but may stimulate inflation even more. Why rock the boat?

What can be done to stimulate investment, especially FDI, which fell substantially last year? A stable, transparent policy structure is highly desirable. The way India treated Vodafone and Cairn in relation to their capital gains is cited by every potential foreign investor. So is the advantage given to Reliance Jio to help it combat Amazon and Walmart in online markets.

Even domestic investors are wary of investing in sectors where favoured ‘national champions’ may suddenly enter on favoured terms. There is not enough trust between the government and investors. Even so, gross capital fixed investment is 33% of GDP at constant prices. This may well be enough to sustain 6.5-7.0% growth.

And employment? Much is written about the difficulty of firing labour. But when a worker moves from the informal to the formal sector, companies have to pay their share of an employee’s provident fund, national pension fund, health insurance, leave travel allowance, one month paid leave, two weeks sick leave and two weeks casual leave. No wonder movement from the informal sector to the formal sector is so slow.

That is why no group will set up garment factories with 10,000 women, as in Bangladesh – the real cost of labour has been hiked by so many non-wage components. However, no political party dares reduce formal sector benefits.

Instead, the budget provides incentives in the form of PF subsidies for new employees. Alas, no company will hire workers just because of a small subsidy. At the margin, a company may employ 1-2 extra employees, not more. Employment will change very little. But our labour laws have not come in the way of miracle growth. So, why risk changes that will cause trade union protests?

Our employment problem is mainly an education problem. Substandard schools and colleges have produced millions of semi-educated, unemployable young people with degrees, but no real skills. Overhauling the entire educational system will take decades. But the problem has not prevented ‘miracle’ growth for two decades. Hence, politicians have no incentive to go for risky reforms.

Here, then, is the irony. India could do better. But a democracy already doing miracle growth has no incentive to take the political risks of radical changes.

This article was originally published by The Economic Times on July 31, 2024.