Along with Taiwan’s Foxconn, Anil Agarwal’s Vedanta plans to set up India’s first silicon fabrication plant (fab) in Gujarat, along with a display glass unit, costing a whopping $20 billion (₹1.6 trillion). Silicon from this project will be sliced into wafers and converted in stages into microprocessors – computers on a chip – and solar power modules.

It is not clear to what extent the processing will be done by Vedanta itself. But Agarwal’s philosophy has always been, ‘We produce raw materials only, and leave processing to others.’ So, it appears that his fab will produce silicon and sell that to others to process.

It Ain’t Too Fab

Maharashtra chief minister Eknath Shinde has complained that the project was supposed to be set up in his state, but has been diverted to Gujarat under political pressure of the previous regime. Vedanta says no, the site was chosen after an independent technocratic evaluation, and politics had no role in it. Business circles say that no project of this size can be entirely free of politics.

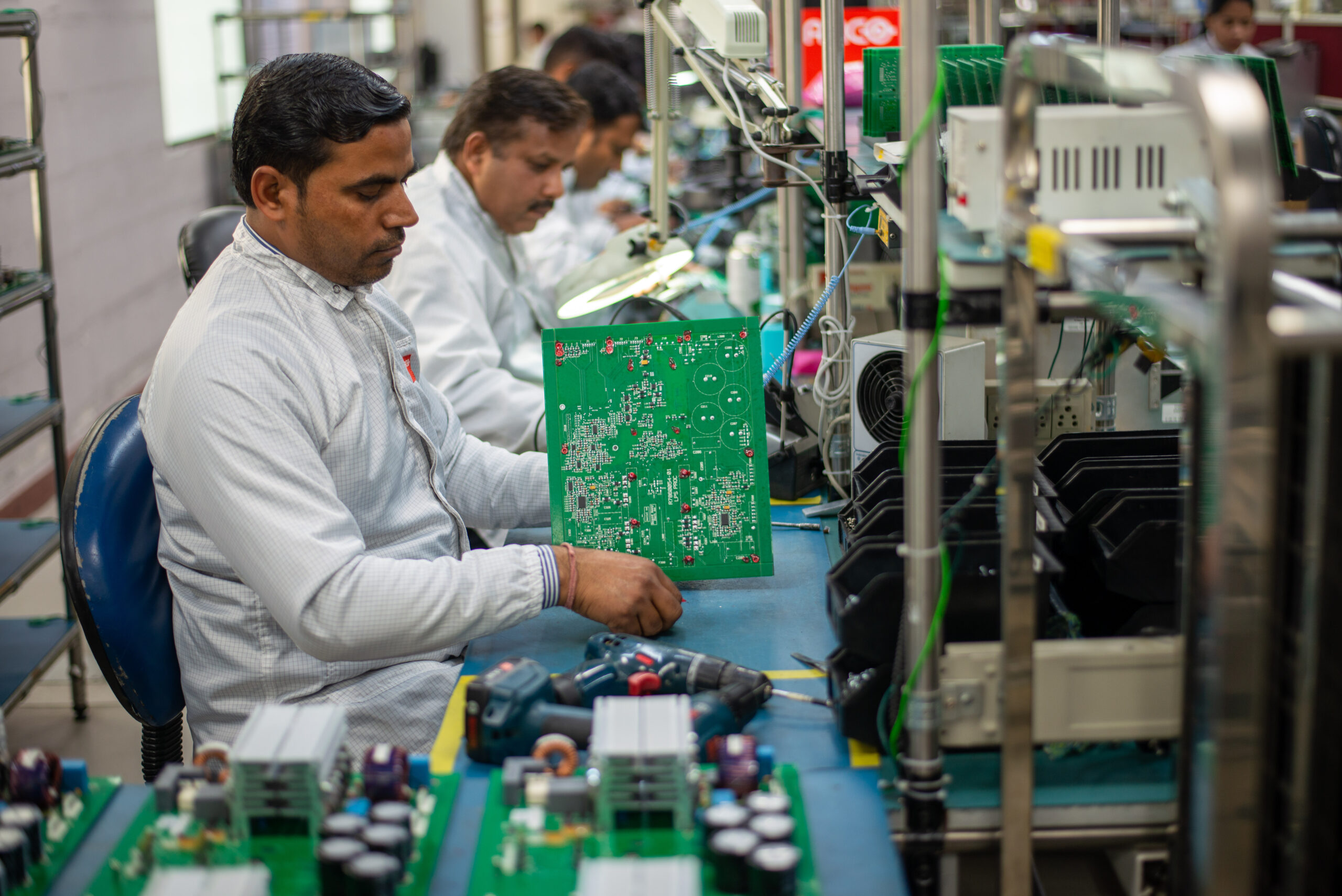

Both states think a silicon fab is the starting point of downstream industries providing lakhs of jobs. The Gujarat government claims that the Vedanta fab will produce a lakh jobs. Whoa! Fabs are enormously costly, create few direct jobs and are being increasingly automated. They can easily turn into white elephants requiring expensive rescues.

GoI has offered a 50% subsidy for silicon fabs. As part of its production-linked incentives (PLI), it has proposed a support package of $10 billion for creating a series of fabs along with allied units like display glass. But if a single project like Vedanta’s costs $20 billion, which threatens to swallow up the entire provision of $10 billion, what about the four or five other fabs to follow? If each gets a similar subsidy, where will the money come from? A 50% subsidy for Vedanta will amount to $10 billion (₹80,000 crore), exceeding the entire central allocation for MGNREGA this year (₹73,000 crore). Priorities, anybody?

No wonder some economists ask whether such subsidies are ‘revadis’, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s term for unwarranted subsidies. Why pour enormous sums into capital-intensive plants creating very few jobs, rather than in MGNREGA? Why not import silicon wafers to be processed in downstream units, avoiding huge subsidies and creating far more jobs for the same investment?

India has no comparative advantage in fabs, which is why a 50% subsidy is required. But India is competitive in chip design, which also yields more jobs. A time will come when India’s industry becomes so large that building silicon plants will become viable. But is this the right time? The most vociferous opponent of the government’s policy is former RBI governor Raghuram Rajan. He worries about the entire PLI scheme, especially the subsidies for fabs.

I am amused at the political battle going on between Maharashtra and Gujarat to get this fab. They have offered to provide free land and freebies on top of central subsidies, thinking that a huge downstream industry will come up around the silicon fab.

This does not follow. Globally, some plants are fully integrated – they produce silicon and convert this into computer chips in the same place. But many giant fabs export the bulk of their production to stand-alone processing facilities across the world. Vedanta’s track record is one of producing raw materials and selling them across the world, not just to Gujarat companies.

Chipped at the Edges

Major US companies do not have their own fabs. Qualcomm, Broadcom and Nvidia are examples, and they produce the most sophisticated chips. India, too, can generate microprocessor companies that do not have their own fab. Maharashtra may, in fact, be very well-off letting Gujarat bear the subsidy burden of the fab plant, and then making merry by attracting plants for processing the silicon. This approach can create a hundred times as many jobs as the fab itself, while avoiding a big subsidy bill.

Globally, a security issue has now arisen. The US is the world leader in producing sophisticated designs for integrated circuits (ICs) and high-end chips. Its companies have the most sophisticated plants for making machinery for the microprocessor industry. Its strength is in design and patents. It has outsourced the production of silicon and chips – its share of global chip production is down to around 12%.

China and Taiwan are the overwhelming producers of silicon and of chips (though not of high-end chips). The US fears it has become overdependent on chips and, that too, on its biggest strategic foe.

Recently, a worldwide shortage of chips forced auto companies across Europe and the US to slow down production, and the shortage is expected to last into 2023.

So, the US passed the CHIPS (Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors) for America Act in July providing $52.7 billion of subsidies over several years to attract fresh investment in fabs and semiconductors. India, too, must at some point build its own fabs. But if India builds just five fabs as big as Vedanta’s, its subsidy bill may be as large as the US’. That looks excessive. We must not rush into this sector prematurely.

This article was originally published by The Economic Times on September 20, 2022.